This FAQ is designed to answer a lot of common questions (and dispell a lot of common myths) around the use of special "R-compound" DOT tires in autocross/solo2.

"Tyre improvements are the quickest way to improve the performance of any car. Generally, the time gain is equal to or greater then all the other factors put together. Put simply, all the many man hours that hundreds of workers put in a team like BAR, coupled with all the many more hours of work by engineers at Honda, amount to the same improvement per season as whatever mysterious changes have been applied to the four black, round things the car is standing on. For, no matter how much power a car produces, it can only go as fast as its wheels can go around. That depends entirely on how much grip a car can get out of its tyres on the tarmac."

- Craig Wilson, Race Engineer for Jenson Button, BAR-Honda F1 2003

(May 2004 - Interestingly enough, BAR (which had been a middle-pack team at best since its inception, despite being one of the most heavily funded teams on the F1 grid) has in 2004 experienced a major leap forward in their race and qualifying pace. The biggest technical change since 2003 and earlier? They switched tire brands from Bridgestone to Michelin.)

Formula 1 makes for an interesting case study in tire performance, as it is firstly the cost-no-object pinnacle motorsport where all the technical ability that can be brought to bear on increasing performance, is; secondly, because the series tends to run on the same tracks with more-or-less similar configurations from year to year; and finally, because, in an effort to try and keep speeds and costs down, the technical rules for the cars have been relatively stable for roughly (as of this writing) six years - meaning that developments in this period tend to be evolutionary rather than revolutionary.

An F1 car from the late Eighties sported the following technical details:

In contrast, a modern (2004) F1 car has:

On paper then, a modern-day F1 car should be very much slower than a late-Eighties car. It is down over 300 HP, it has much less rubber on the road, it has less downforce, is narrower, and it lacks the computer-controlled magic suspension. Despite this, lap records on tracks which remain in current use (from the late-Eighties period) and lap records from year to year within the current period, are falling at the rate of roughly one second per year. The current cars are vastly faster than their earlier bretheren.

Some of this improvement can be attributed to developments to the cars themselves, particularly on the aerodynamics fronts. The F1 teams have access to more and better wind tunnels, and more (and much faster) computers, such that computer modelling and CFD is allowing the extraction of ever-increasing levels of efficiency from ever-decreasing amounts of aero surfaces to work with. This, however, is incremental improvement. The truly startling improvements in lap times coincide very closely to the occurrence of a single event:

The arrival of Bridgestone in F1.

Prior to 1998, F1 had a single tire supplier, who supplied each team with the exact same tire. There was some flexibility in compound choice, but for all intents and purposes F1 was a spec tire series. With no particular incentive to make the cars faster, that tire supplier (Goodyear) chose instead to focus on wear and reliability.

With the arrival of Bridgestone, a tire war developed. With reputations and global sales on the line, the performance-enhancing gloves came off, and lap times started dropping - fast. When the FIA tried to counter by restricting the width of the tires and by adding contact-patch-area-reducing grooves to the tires, there was no effect on lap times, as the tire engineers just made the tires that much more effective.

Unable to keep up with the rapid development pace, Goodyear pulled out of F1, and was promptly replaced by Michelin, such that the continued escalation in tire performance has continued right up to the current day. Normal F1 practice is to build a new and different car every year, but some times have recently carried over cars from previous seasons with relatively few changes, and these cars will routinely outrun their times (on the same tracks, often with the same drivers) with the latest-specification tire.

It is not at all uncommon for cars to outrun the previous year's qualification times during the race proper, and for qualification times that would have taken pole 12 months prior to instead qualify near the back of the grid - with the only substancial difference in the car being the tire construction.

(The major exception is reliability. F1 motors, chassis etc have made only incremental advances in raw performance potential, but on the reliability front the cars are light years ahead of their precursors - so it's not as if the chassis and engine people have been sitting on their hands!)

The lesson here is clear: The single most important determinate of car performance is the tire it is running on.

The following text was provided by a long-time, top-level autocrosser who was neck-deep in all the various tire company shennaigans over the years. He has asked me not to reveal his name, but he has allowed me to quote his story.

late 70's: Even the bias Hoosier Street TD is allowed in Stock, and for the larger cars where they have sizes, it is the only thing to have.

1979: Hoosiers dis-allowed in Stock; rules much like current STS in effect, with much the same result: At the most competitive levels of the sport, it is much like now - there are only one or two tires that are truly competitive. For the larger cars, the advent of the Pirelli P7 is a blessing; in the smaller cars a run on the imported Phoenix Stahlflex makes it the tire to have.

198?: Retreaded tires disallowed as some retreaders apply tread slabs of significantly softer rubber to the P7 carcass. Some competitors (and retreaders!) claim huge cost savings, discrimination, restrait-of-trade, etc.etc. One small magazine publisher sees a financial advantage to allowing such tires in the events run by the club association he has founded.

1982: [new to the market] Pacific Rim manufacturer, to make a name for themselves as they enter North American markets, approaches SCCA et.al with the "Yokohama A001R", and promotes it as not simply softer rubber, as with the banned Hoosiers / retreads, but as a major technological breakthru, giving improved performance without sacrificing wear.

SCCA's Club Racing Comp Board buys this hooey and allows the tire in Showroom Stock. The SEB follows suit. At that year's SCCA Convention, the other tire manufacturers present (Goodrich, Goodyear, Bridgestone) walk out of the convention meeting in total, complete and utter disgust at this travesty.

Pandora's Box has been opened as to soft compounds, further complicated by the fact that Yokohama made the 001R in only small sizes.

Balance of the 80's: Tire Wars. Goodyear comes in with the VR50S in 1985, so by 1985 the larger cars have something that will run with the Yoko. Goodrich introduces the TA R1 in 1986.

At the extreme, there were tires that lasted 4 runs. Tires that were grooved slicks with DOT labels. Tires that were available to only SOME favorite drivers. Tires in 4 seperate (secret) compounds. Tires built and used only at the Solo II Nationals then returned.

SCCA responds with the appropriate rules to address these abuses, including:

- claiming rules

- equal distribution rules

- seasonal change restrictions.

(And note that there were similar and parallel things going on in Club Racing.)

Much agonizing, ashes, sackcloth, recriminations, and ideas for change promoted during this time, most of which were discarded as truly un-workable, impracticable, and un-enforceable.

Marvin Rifschin from McCreary Tire (?) says, at one SCCA Convention meeting (to the nods of agreement from every other tire company rep on the panel) "there isn't a rule you can invent (i.e., treadwear, durometer, etc. etc.etc.) that we can't get around if we really want to. We can win any competition/race series we want, no matter what rules you write".

The 90's: A return to some level of sanity & stability with part due to the rules, but more due to the limits of budgets of the tire companies. Bridgestone, Yokohama, BFG, MickeyThompson, Goodyear, et.al all played in these performance markets & left, tired of the constant escalation.

And what we are left with is tires in Stock/Street Prepared that are relatively short-lived and expensive, but since all but two of the players have been run off, relative stability and a sort-of even playing field.

The constant during all of this is Hoosier, staying with the programs no matter the competition or the rules.

There are two key points that need to be recognised here:

"there isn't a rule you can invent that we can't get around if we really want to. We can win any competition/race series we want, no matter what rules you write"

From my conversations with other "contract" drivers from this era, it seems that there were many different tiers or levels to driver contracts. Some drivers were special; but some were more special than others, and many on the lower tiers were not aware of the level of extra support given to drivers higher up on the pyramid from them.

This latter behaviour jibes with a story I was told about the Firestone vs Goodyear tire wars at the Indy 500.

This story was told to me by a former Indy team engineer. Unfortunately, this isn't a direct quote - I'm paraphrasing from memory:

"I went to the Goodyear trailer to get the latest tire specs from their engineers, and was handed a file folder containing the spec sheets. But when we compared these specs to the specs we had derived from the data analysis, they didn't match, and setups based on the specs Goodyear provided us didn't work.

So I went back to the Goodyear trailer, thinking that there must have been some mistake. At the trailer this time was the head of Goodyear's motorsports engineering division. When I complained about the specs not matching, I was asked to provide a copy of my calculated specs. Their head engineer examined them, and nodded, and the mechanic reached into a different drawer and pulled out a file folder with a different colour cover on it. The specs in this folder were much closer to what we had derived, and setups based on these specs worked.

It was clear to me that the first set of specs were a kind of test, to separate the real engineers from the pretenders, and to perhaps mislead the Firestone engineers if a copy of these false specs fell into their hands."

But even that tale of deviousness pales in comparison to what happens at the highest levels:

"I was taking a racing engineering and vehicle dynamics course, presented by an ex-F1 race engineer. He was showing us a video of a tire testing machine in operation, putting a current (2002) F1 tire through its paces. This machine consists of a huge hydraulic arm that rams the tire into a steel belt (constructed like a giant upside-down belt sander) and then scubs it across the belt to simulate lateral loads.

The purpose of the video was to demonstrate sidewall deflection under full load, and indeed the tire adopted a shape not unlike a tea saucer at maximum lateral load. But during the course of the video, something else happened: as the tire was scrubbed outboard, it left distinct treadmarks on the belt. But as the tire was scrubbed back inboard, the marks vanished.

At this point, the instructor paused the video, pointed out the missing rubber marks, and stated "F1 tires are designed such that the tire compound has a high affinity for its own compound, but a low affinity for the compound of a competing tire brand. In other words, the rubber you put down on the track is sticky to you, but slippery to your competetors. Here you can see the tire sucking up its own rubber from the belt"

When another student asked how they could tell what the competetor's tire compound was, the instructor replied "The F1 teams don't own their tires; they must return them to the manufacturer after the race. It is standard practice to run offline on the cool-down lap after the race, to try and pick up as many marbles as possible in order to add weight to the car and help make weight in parc ferme. The tire engineers can then scrape off these marbles and analyze their construction"

- Dennis Grant

The natural rejoinder to this is something along the lines of "The tire companies aren't willing to commit that much time/money/resources to autocrossers".

While it is certainly true that there is a cost/benfits analysis going on every time a tire company does anything, do not make the assumption that autocross tires are in any way low tech.

From Paul Haney's book on tires, The Racing and Performance Tire

I asked Bruce [Foss, Hoosier product manager] about camber. "Are you building some camber into the ['94 NASCAR] tires?"

"Yes, we are," Bruce answered. "BF Goodrich emphasized that a while back in autocross tires to give more grip with cars that were prevented by rules from adding camber. That's the situation in NASCAR, where the rules and the solid rear axle housing keep the car form having the optimum abount of camber. We're using asymmetrical sidewalls - stiffer inside sidewalls - to generate camber thrust and keep the contact patch in place during cornering"

- Paul Haney "The Racing and High Performance Tire" 2003 P140

Not only is this a case of autocross tire technology being utilized in a higher level motorsport, it's also worth mentioning that the asymmetrical-sidewall, "pre-cambered" tire technology being discussed here was a feature of the BF Goodrich R1 tire, a competitor's tire, and not natively developed by Hoosier. So not only do we have evidence of technology trickling up out of autocross to higher series, but also evidence of technology jumping corporate lines.

So while autocrossers may be small fish compared to F1 and NASCAR, there is evidence that we get our share of research and development - and that the R&D we do get is every bit as sophisticated as used in higher series.

The bottom line here is that if a tire company feels that it is in its best interests to do so, it can and will develop an autocross tire designed to go faster than its competitors.

In the face of all this evidence that there was little to nothing that they could do to keep the tire companies in check should they decide to attempt to win, the Rules Barons did the wise thing and allowed the use of DOT-R compound tires in all classes. The only standards that the tire companies were required to meet are:

The primary reasons behind these restricions are as follows:

To date, this has proven to be an acceptable compromise. While there are still "tire wars" in terms of performance developments between manufacturers, big steps forward tend to happen on a season-by-season basis, and the tires are made availible to all. The downside is that tires tend to wear quickly and are generally unsuitable for street use.

The current average wear rate of a National-level team, attending 4 ProSolos, 2 National Tours, and Nationals, is 2-3 sets of tires per driver per year. Prices per set run between $600-$1000 for top-level tires, with larger sizes being more expensive. Teams competing at lower levels tend to stretch their tires longer, and 1 set per season is not at all unusual.

(Compare to an ALMS team, which burns 12-14 sets per weekend, at $1600 per set!)

By adopting the current DOT-R tire rules, a great deal of stability has been achieved, at the cost of requiring any autocrosser who wishes to be reasonably competitive to, as a minimum, purchase a second set of wheels and tires and change from street tires to "race tires" at the event.

Unfortunately, these conclusions and the wisdom behind them was not long remembered, and in 1999, a class was introduced that resurrected the concept of the dual-purpose street/competition tire. Adopted as "Street Touring" (later changed to "STS") this class used a treadwear cutoff rule to serve as the line between the "real street" and "race" tire. While initially envisioned as a means to attract younger (and theoretically poorer) members into the sport, it was very quickly adopted by a demographic that wanted to drive nearly-stock cars on street tires - theoretically removing the need to change tires at the event, and cutting tire expenses in general.

A further "street tire" class that used the same tire eligibility rules but allowed more car modifications, was adopted as "STX" in 2001.

But by intoducing these classes, the SCCA has opened the door to history repeating itself, and all the pain and suffering that goes along with that.

At issue here is the fact that, at the National level at least, the drive to succeed is so strong (and the performance level of tires so effective) that top-level competitors will agressively seek out the best tires they can find. All other factors, particularly cost and life, are subservient to this need.

At the 2003 Solo2 Nationals, I saw STS competitors with multiple brands of tires mounted up and ready to go, should any one brand prove superior. Cars with multiple drivers were switching brands from driver to driver and run to run in search of the best performing tire.

Accordingly, if a tire company decides that it wants to produce a superior tire, then there are competitors who will use it, no matter the cost. Once that tire is identified, the general STS competitor base will be forced to either migrate to the new tire, or be uncompetitive.

One of the most common rebuttals to the idea that the tire companies will eventually attempt to go after the STS/STX tire market in the aggressive manner they did with Stock and SP in the '80s is something along the lines of "The STS market is too small to attract the interest of the tire companies. It's not worth the effort for them."

Presented is a case study that shows just the opposite - not only are the ST classes on the tire OEM's radar, they have been since the very beginning of the class.

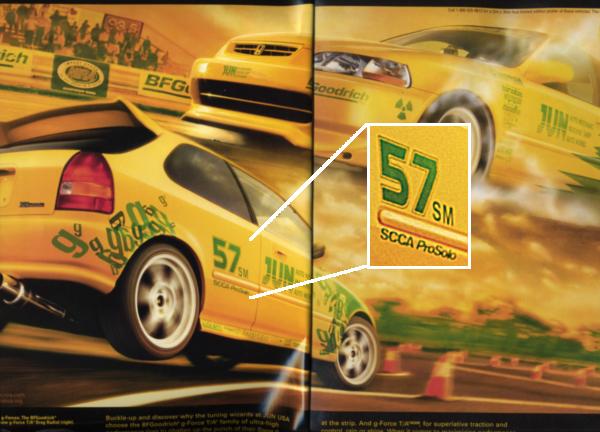

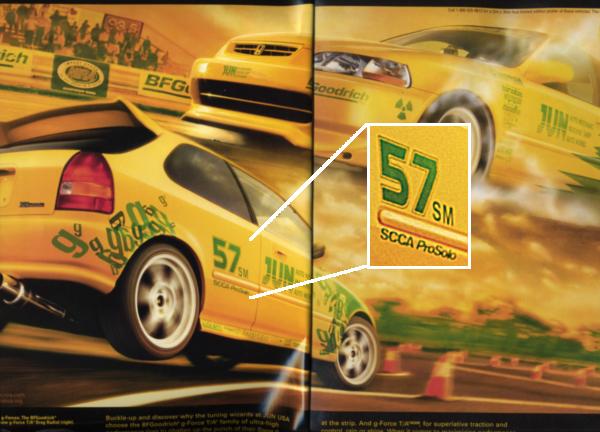

BF Goodrich planned to launch a pair of new tire models in the summer of 2001 - the BFG T/A KD ultra-high performance, dry-condition street tire, and the BFG T/A Drag Radial street/strip drag racing tire. To support the product launch, a pair of Honda Civics were prepared with the aid of JUN USA, and these cars were to be given away in a contest. Magazine reviews of the cars (and their tires) were to be published concurrent with the product launch, and these cars - a drag car for the T/A Drag Radial, and an autocross car for the T/A K/D - were to be heavily featured in BFG's advertising.

The tires were launched in July 2001. The cars were the cover story in Super Street magazine, and the following ad ran as the 2-page inside cover spread on that same issue.

It is interesting to note that the autocross car was released in the livery of an SCCA ProSolo "SM" - Street Modified - car, as shown in the inset.

This ad ran as the inside cover spread in Super Street and Sport Compact Car for the next year.

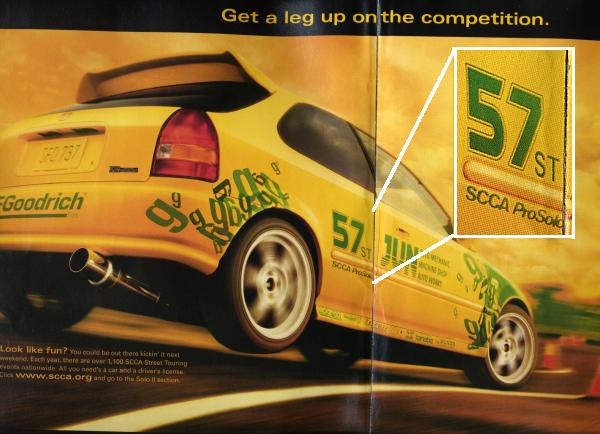

By July 2002, BF Goodrich had figured out that SM was a class for DOT-R compound tires, and that the T/A KD was not an appropriate tire to market in that context. Accordingly, the "SM" on the side of the autocross car was Photoshopped out and changed to "ST". But perhaps even more interestingly, the inside cover ad had been changed to feature the autocross car and Street Touring exclusively. From the July 2001 Sport Compact Car :

The text that goes along with the ad is perhaps even more instructive:

Look like fun? You could be out there kickin' it next weekend. Every year there are over 1,100 SCCA Street Touring events nationwide. All you need is a car and a driver's licence. Click www.scca.org andd go to the Solo II section.

'Cause you'll be top dog with a set of BF-Goodrich g-Force T/A K/D tires. SCCA Street Touring competition is for street-legal sport compacts like yours: Suspension mods. Body kits. And real street tires, not some zero-tread-depth R-compound specials. And in Street Touring, g-Force T/A KD tires rule: Winning the 2000 National Chanpionship. Winning the 2001 Ladies National Championship. Pretty much what you'd expect of tires that registered the highest roadholding number of any US-spec production vehicle Car and Driver wrote about in 2001. g-Force T/A KD tires. 'Cause even if you don't race, you wanna be the lead dog.

- BF Goodrich ad copy, July 2002 Sport Compact Car

Now it is a little dangerous to attempt to read too much into these ads and from them, intuit the subsequent intentions of BFG. In particular, it is important not to assume that the T/A KD was designed as an all-out assault to dominate the upper ranks of STS. From reading the ad copy, it seems that BFG either understood the nature of the line they were walking - ultimate performance vs street suitibility - or perhaps were trying to put a positive spin on a tire that was under-performing its design (the g-Force R1 DOT-R tire from the same era was a complete disaster)

But it is important to note that not only was autocross and ST in particular not only on the radar of a major tire company, but in fact formed a major component of their advertising copy of the day. The text of the second ad makes it sound like Street Touring is the only class being run by the SCCA!

The current STS/STX base their tire regulations on a single factor - the value of the treadwear rating stamped on the sidewall of the tire, as required by the DOT Uniform Tire Quality Grading Standard 575.

The DOT Tire Grading StandardThe treadwear standard defines:

(2) Performance

(i) Treadwear. Each tire shall be graded for treadwear performance with the word TREADWEAR followed by a number of two or three digits representing the tire's grade for treadwear, expressed as a percentage of the NHTSA nominal treadwear value, when tested in accordance with the conditions and procedures specified in paragraph (e) of this section. Treadwear grades shall be expressed in multiples of 20 (for example, 80, 120, 160).

The STS/STX rules use the treadwear rating as a cutoff point - any tire with a treadwear value below the cutoff is considered a "racing tire" and is banned.

The implied assumption here is that autocross performance scales with the treadwear value, such that lower treadwear values imply better autocross performance. The other assumption is that there exists a cutoff value, such that all tires with treadwear values equal to or greater than the cutoff value (within reason - nobody expects a 600 treadwear rock to perform very well) will wear at acceptable levels such that the car/tire can see daily street use plus at least one full season of autocrossing without having to change tires. (Compare to DOT-R tires, which are pretty much precluded from daily street use and typically last 60 runs).

The worst-case scenario for STS/STX is the introduction of a tire that provides performance at a level such that all competitors must use this tire if they wish to be competitive, that meets the current treadwear cutoff value, but wears at or near DOT-R rates. The situation is further worsened if the unit price for these tires approaches that of the DOT-R tires.

Once these conditions are met, then you might as well be on DOT-R tires and enjoy the extra performance. But as has already been demonstrated, the primary attraction of (at least) STS is the ability to use long-wearing, dual-purpose tires. The mod mix provided by STS is not attractive enough on its own to sustain a loyal competitor base, as was shown by the abject failure of STR (ST rules, but DOT-R tires) to gain any sort of competitor following.

In order to judge the effectiveness of the treadwear cutoff rule in ensuring the performance and longevity of an STS tire, we need to examine the following three factors:

First, let's examine the treadwear grading procedure:

(e) Treadwear grading conditions and procedures

(1) Conditions.

(i) Tire treadwear performance is evaluated on a specific roadway course approximately 400 miles in length, which is established by the NHTSA both for its own compliance testing and for that of regulated persons. The course is designed to produce treadwear rates that are generally representative of those encountered by tires in public use. The course and driving procedures are described in appendix A of this section.

(ii) Treadwear grades are evaluated by first measuring the performance of a candidate tire on the government test course, and then correcting the projected mileages obtained to account for environmental variations on the basis of the performance of the course monitoring tires run in the same convoy.

(iii) In convoy tests, each vehicle in the same convoy, except for the lead vehicle, is throughout the test within human eye range of the vehicle immediately ahead of it.

(iv) A test convoy consists of two or four passenger cars, each having only rear-wheel drive.

(v) On each convoy vehicle, all tires are mounted on identical rims of design or measuring rim width specified for tires of that size in accordance with 49 CFR 571.109, S4.4.1 (a) or (b), or a rim having a width within ¥0 to +0.50 inches of the width listed.

[...]

(v) Subject candidate and course monitoring tires to break-in by running the tires in the convoy for two circuits of the test roadway (800 miles).

[...]

(viii) Drive the convoy on the test roadway for 6,400 miles.

In a nutshell, the testing procedure is to drive a convoy of cars over a series of public roads, taking note of the wear rate, and comparing the wear rate to a set of standardized tires that make the same journey.

Interestingly enough, the total course length of the test is 7200 miles. Assuming an average speed of 55 MPH, and a 40-hour work week, it takes three and a half WEEKS to test a single tire model!

From this, we observe that: